I live in the Armory neighborhood of Providence, and mostly use the Westminster Street corridor to get from my house to downtown. It’s an up-and-coming commercial district, with the “hottest new bar” in Providence and many new businesses interested in opening on it.

But, as with even the best, most vibrant commercial strips in any city, there are some lulls in Westminster’s streetscape. Long, blank walls abut the sidewalk on buildings clearly not interested in people walking. Fences impart a “keep out” message. And the most street-deadening feature of all, parking lots either between a building and the sidewalk or worse, taking up a whole lot. When these subconscious barriers are present in a streetscape, they make the neighborhood less walkable, both by making it feel less safe and like it’s a longer walk than it is.

What features would be more welcoming; what could property owners do to encourage potential customers to stop by and spend money? Commercial buildings can have large unobstructed windows to encourage window-shopping (it works for services as well as products). Parking lots can be tucked behind buildings so they don’t create a vacant feeling on the street. And if a property must have a fence for security reasons, they can steer clear of chain link fences and fences that obstruct pedestrians’ view, instead preferring shorter, black ornamental iron fences. And the best thing of all for the streetscape is the presence of lively businesses that have a lot of people coming and going.

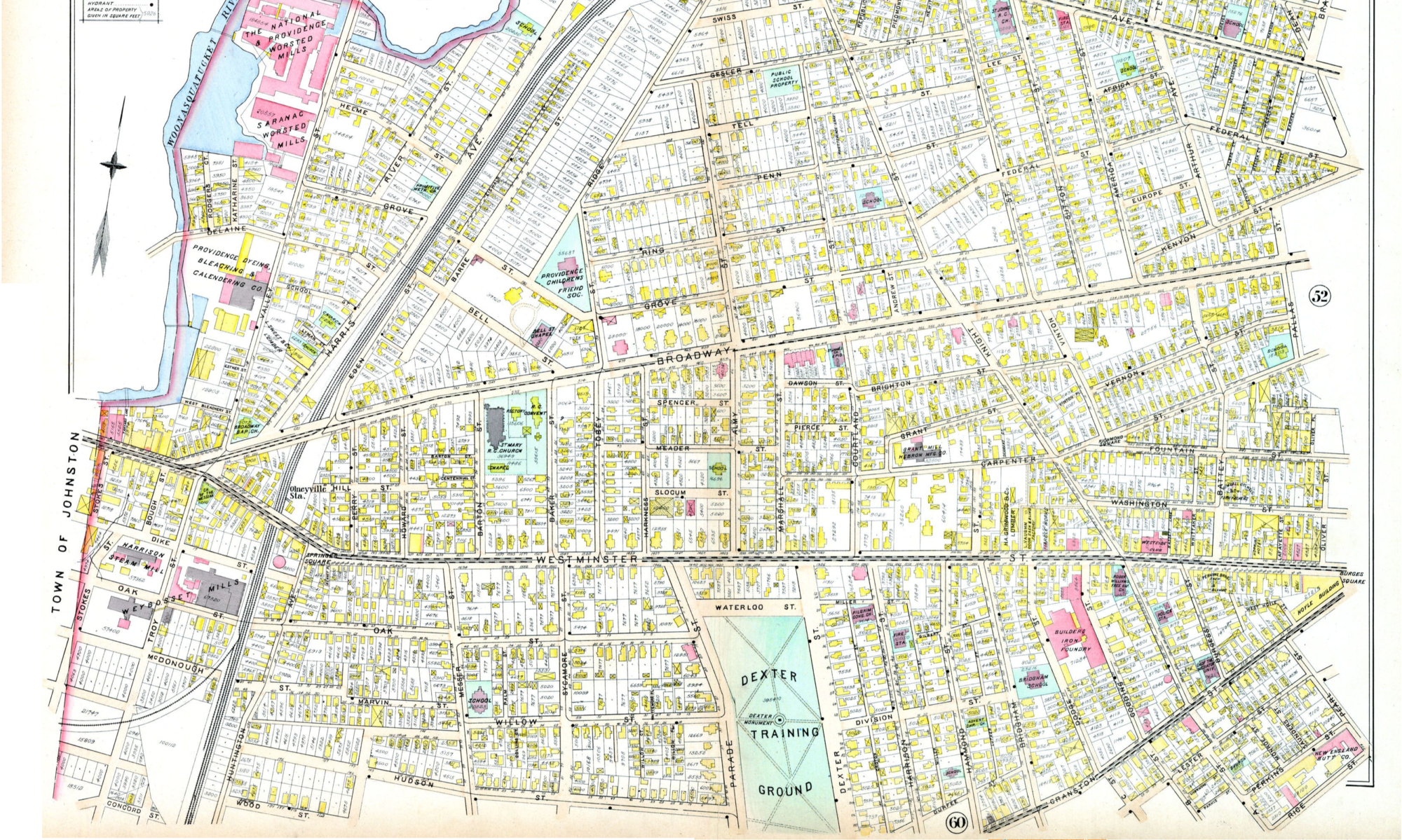

I made a map of the bright spots and dull spots on Westminster Street on the West Side, from highway to highway. These assessments are subjective and perhaps incomplete, but are based on the principles above.

A few zones of note along the street:

- On the east end of the street is Canonicus Square, at the Dean/Cahir crossing. This is the most vibrant part of the streetscape, despite the south side of the street being not especially welcoming to walk on due to the blank facade of the housing tower and the street-adjacent parking lots by the high schools. Why? Because it has a vibrant commercial strip along the north side. Many of these businesses have big windows that invite passers-by to peek and see what’s going on.

- The first zone in the middle of the corridor that makes walking less desirable are the one-two punch of the Citizen’s Bank and John Hope House parking lots. These two massive asphalt canyons on the south side of the street make the walk from Winter Street to Bridgham Street seem extremely long. There’s not much across the street from them to invite pedestrians, and John Hope even has an opaque hedge blocking your view. This section of the street sends the message that is for cars to get through as fast as possible and not for people to spend any time.

- The second zone in the middle of corridor that could use improvement is the north-side block between Courtland Street and Bridgham Street. There’s one massive vacant parking lot for sale with a big chain link fence around it, Paper & Provision Warehouse that is an active business but features a street-adjacent parking lot and a blank brick facade with no windows, and then another brick building whose facade is essentially blank. The primary two things I can conceive of making this better would be the sale of that vacant parking lot and its development as something people want to walk by, or the renovation of one or both brick building to add bigger windows.

- There is a welcoming zone on the western half of the street as well. Between Dexter Street and Parade Street, there are a number of welcoming facades, including the West Side Diner, Community MusicWorks, Loie Fuller’s, and Healing Paws. These good street frontages combined with other facades I classified as neutral (Mi Ranchito with tinted windows, La Perla Fruit Market with covered windows, WBNA set back from the street with hedges obstructing view) make the walk from Parade Street to Fertile Underground seem not very far at all.

Other factors that would make Westminster a more lively commercial corridor would be the addition of bike lanes and sidewalk bump-outs at crosswalks (especially at the wide cross streets Parade & Dexter). Also, it doesn’t take much to fill a dead space on a streetscape. If a really awesome business moved in to either of these dead zones, even across the street from the biggest problem area (e.g. Julian’s Pizza) it would do a lot to enliven the streetscape for the benefit of all businesses and residents of the neighborhood.